(Akiit.com) Earlier this week, Her Majesty the Queen, Elizabeth II, was laid to rest in St. George’s Chapel in Windsor. Several times in the days prior, the queue to see Her Majesty’s body Lying in State in London has been closed, for reaching maximum capacity. Days before, mere hours after it was announced that she had passed away, crowds began appearing outside Buckingham Palace. Somber silence and quiet reverence hung over the crowd, broken only by spontaneous outbursts of God Save the King.

To an outsider, this outpouring of grief may seem silly, pointless, or even contrived. Despite the jokes of “have you met the Queen?”, it goes without saying that so many of us, who have in the last week shed tears, joined with family and raised a glass with friends, never actually met her. At least, not in the literal sense. But every time we opened our wallets, sent a letter, paid our taxes, or did anything official, we would be greeted with her face or crest, smiling at us with that warm, kind face that became a constant of daily life.

And some of our traditions may even seem frivolous. Many mockeries from around the world – and even a few at home – have been made of the Accession Council, the King’s Address to the two Houses of Parliament, the costumes, the rituals, all of it. Yet there’s a certain pride in knowing that we really do it better than anyone else.

How can we explain why British people love the monarchy? How do you explain that which can only be felt, can only be lived? It is not rational; you do not know it, you only understand it. And therein lies the secret – monarchy is felt by the British. There is no historic moment of national unity to point to, but we do have this shared focus of affection that offers us a way out of the mundanity of life, and the division of politics.

This “way out” can be understood more clearly if we realize that the monarchy is not necessarily the object of our affection itself, but guides Brits in the direction of a deeper understanding of themselves than the mundanity of day-to-day life. Monarchy, instead, is the physical embodiment of the national myth, that we are more than just a group of individuals who can be found on a set of damp, soggy islands on the edge of Europe; but that we are a single people bound, not by a historic founding or a codified constitution, but by an evolving and living institution that stands above and apart from our divided interests. Or as the British philosopher Sir Roger Scruton put it, “This was the real reason for the English attachment to monarchy as a form of government. The king or queen symbolized the personhood of England – its unchanging and vigilant claim on our affection.”

On paper, this might seem strange to Americans. After all, the American founding was not just an explicit repudiation of the concept of hereditary monarchy, but of the very monarchy the late Queen inherited. There is more in common than one might imagine, however.

In 1835, Alexis de Tocqueville observed that “Americans of all ages, of all conditions, of all minds, constantly unite.” Indeed, American civic life revolves around an unmistakable sense of national solidarity. This is often expressed in clearly visual ways. Where Britain has royal processions, parliamentary pomp and circumstance, and the yearly Last Night of the Proms, America has fireworks on the 4th of July, the Stars and Stripes on every street corner, and the national anthem before sports events.

Though the traditions and expressions thereof differ, both nations root themselves in a commitment to upholding the values that make them unique. This national ethos provides a reference point that guides and structures the otherwise random procession of daily life.

America’s republic and Britain’s monarchy also share interesting constitutional similarities. The U.S. government is subordinate to a living Constitution that upholds certain inalienable, God-given rights, whilst the monarch, reigning through Parliament, swears to uphold and protect the integrity of the realm and the freedom of its subjects. Though very different political systems, both are rooted in what Yoram Hazony calls “Anglo-American conservatism,” or in other words: “the desire to learn what holds societies together, benefits them and destroys them.”

Both the American and the British experience therefore embody a certain transcendence in political and national life. Indeed, as the philosopher Michael Wyschogrod observed, “[…] constitutional restrictions on popular sovereignty imply reliance on an authority that is greater than human.”

Where most liberal democracies nowadays are guided less by a sense of national purpose and tradition, and more by the deterministic machinations of majoritarianism, America and Britain retain a sense of larger-than-life transcendence in their politics. Call it superstitious, old-fashioned, or whatever you like, but it works.

Ultimately, we believe this is why so many are transfixed by a nation’s grief over its Queen. No matter one’s opinion of the monarchy, it’s hard not to be moved by the outpouring of solidarity in Britain. We are confronted with a unanimous expression of intense grief that is raw, vulnerable, and deeply human. It reminds us of our better nature. It shows us that there is something beyond the individual, something meaningful that binds people together, like a string weaving through the generations.

Many modern cultures have forgotten how to grieve properly. But countries with a vestige of national solidarity understand it better. Though they are of course vastly different situations, we are reminded of the solidarity in mourning that America displayed after 9/11. For a moment, everyone was just American – neither Republican nor Democrat, urban or rural, white or black.

Unfortunately, however, in the same way America has its cranks, anti-monarchists are attempting to capitalize on Her Majesty’s passing. A generational divide is growing, where older generations remain staunchly pro-monarchy, whereas younger people are increasingly unsure. This sense of malaise is familiar to American conservatives, worried that younger generations are rebuking the nation’s founding and abandoning traditional American values.

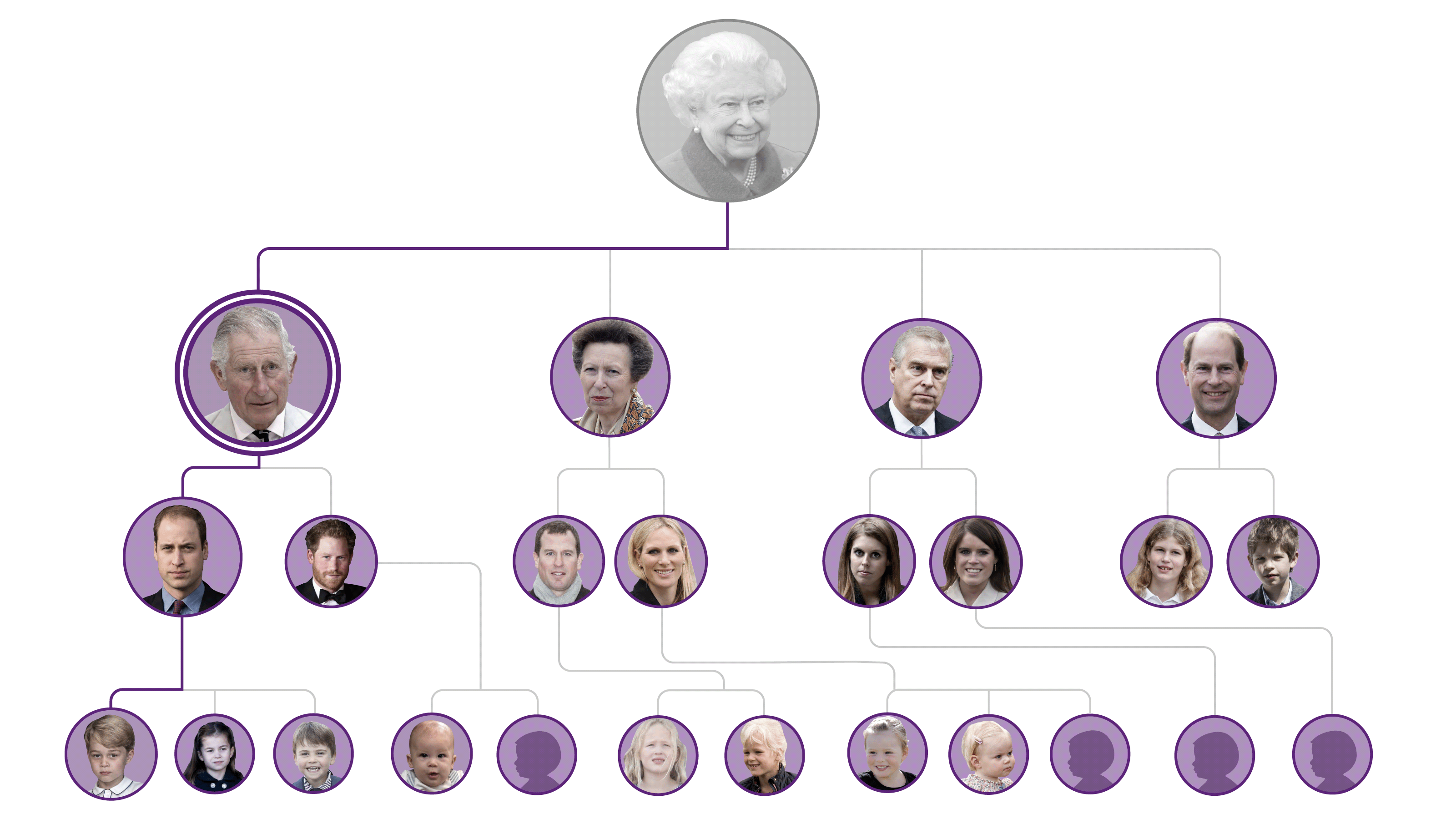

Yet, Charles’ immediate and seamless accession to the office of King helps undo this challenge. The Second Elizabethan Age may have ended, and a new Carolean Age begun, but they are simply links in the great chain of British history, binding us together, young and old, past and future. The American founding offers a similar, central focus of national loyalty, both as a statement of self-determination and an ideal vision of what the political community should look like. Both the British monarchy and the American Constitution therefore bring those they touch together, and offer an ideal to live up to.

Columnist; Christopher Barnard & Jake Scott

Official website; https://twitter.com/chbarnard

Leave a Reply