(Akiit.com) The U.S. Senate recently reduced the sentencing disparities for possession of powder cocaine and crack, from 100-1 to 18-1. That’s hardly progress…

The U.S. Senate recently reduced the sentencing disparities for possession of powder cocaine and crack, from 100-1 to 18-1. That’s hardly progress.

Nothing symbolizes the conflicted state of U.S. race relations more than the tortured odyssey of crack cocaine. Federal sentencing enhancements for the drug, which we now know is pharmacologically indistinguishable from powder cocaine, date to the Reagan administration. They have had an astonishingly injurious impact.

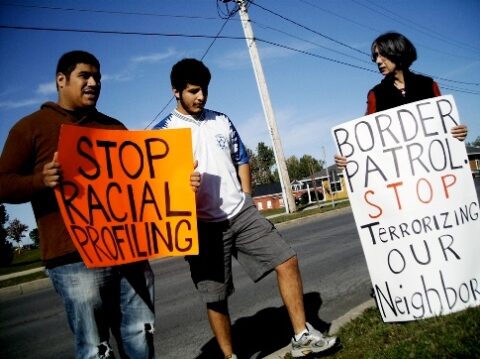

Although surveys show that most users of cocaine, in all its forms, are white, African Americans and Latinos account for 96 percent of crack convictions, most of them low-level street dealers. Because the mandatory penalties are so harsh–possession of 5 grams yields a minimum sentence of five years–African Americans with crack raps are now serving as much time in federal prison as whites convicted of violent offenses. Federal District Judge Robert Sweet calls it “Jim Crow justice.”

The U.S. Sentencing Commission has proposed relaxing special penalties for crack since 1991, arguing that it would do more to reduce racial inequality in criminal justice “than any other single policy change.” Yet Congress has declined to act for a generation. With the election of Barack Obama and Democratic majorities in both houses, reformers hoped for a breakthrough at last. But when the Senate finally reached a deal on the Fair Sentencing Act in March, it only partly closed the penalty gap. Under the current rules, crack possession is treated 100 times more severely than powder possession, based on drug weight; under the new rules, which the House is expected to approve before the summer recess, crack possession will be treated 18 times more severely.

“I gave a little, and they gave a little,” said Sen. Richard Durban (D-Ill) of his negotiations with Republicans, who insisted on maintaining unequal sanctions. The result is a sort of progress, but it means that tens of thousands of crack defendants, the lion’s share of them young black men, will continue receiving longer prison terms than their coke-snorting counterparts–and with no justification supported by evidence. Seven score years after the end of slavery, America still can’t do better than halting steps toward equality.

Because of their undeniably inequitable outcomes, the nation’s crack laws have come to represent the persistence of de jure discrimination in the post-civil rights era. But they are only a fraction of the problem.

The expansion and hardening of criminal justice writ large has had similarly pernicious effects. A half-century ago–before the Freedom Rides and the March on Washington–African Americans went to prison at about four times the rate of whites; today, African Americans go to prison at seven times the rate of whites. Fifty-six years after Brown v. Board of Education, black men in America are more likely to go to prison than graduate from college.

These statistics are widely known and shamefully tolerated, but we are only just beginning to reckon with their historical significance. In my book, Texas Tough, I argue that the rise of mass imprisonment constitutes a watershed retreat from freedom not unlike the collapse of Reconstruction. In the aftermath of the Civil War, black Americans made tremendous strides toward equality under federal protection, only to be driven back to second-class citizenship by a protracted campaign of white terrorism led by the Ku Klux Klan. The result was convict leasing and Jim Crow segregation, which deferred the full promise of emancipation for a century. As W.E.B. Du Bois put it, “The slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery.”

In our own time, the punitive revolution in criminal justice followed a similar path in the wake of civil rights. White Southern conservatives reluctantly yielded to integration but managed to reclaim votes and legitimacy by getting tough on crime. Zero tolerance, mandatory minimums and merciless drug statutes were not just responses to illegality but fearful, politically calculated reactions against urban disorder, youth rebellion and black mobility. In short, modern America has institutionalized the advice of Texas’ arch-segregationist, U.S. Sen. Joseph Bailey, who once remarked, “I want to treat the Negro justly and generously as long as he behaves himself, and when he doesn’t, I want to drive him out of this country.” Through the prison system, we have done just that. Although Jim Crow has been banished from the free world, the Joshua generation is being driven into captivity.

At the start of the Obama era, there is some hope for change. Largely in response to government-revenue shortfalls, politicians across the country are trying to rein in their runaway prison bureaucracies, which now devour $70 billion a year. At the state level, probation and parole reforms have contributed to a moderate decline in the nation’s inmate population for the first time since 1972. In Washington, in addition to the deficient crack bargain, Congress is considering a national criminal justice commission to recommend policy changes across the board, from indigent defense to reentry. These steps show promise, but after 40 years of warring on drugs and building prisons, courage and persistence will be required to significantly reduce racial disparities in criminal justice and downsize the world’s largest penal system.

To get smart on crime, President Obama will have to make meaningful criminal justice reform a top priority, on par with health care or banking regulation. To finish the work of Abraham Lincoln, this newcomer from Illinois will have to issue a second Emancipation Proclamation, throwing open cell doors in the federal system and nudging states to do the same.

Written By Robert Perkinson

Leave a Reply