(Akiit.com) New Yorkers used to say, ”today, everybody is Irish” on St. Patrick’s Day, recognizing important facts about the journey the Irish made through social barriers and celebrating their culture and achievements. People also say there is a sense in which everybody in New York City is Jewish. The culture has been indelibly marked by the presence and accomplishments of the Jews.

February is Black History Month. Are we who are not black ready to say that, in February, we are all African American? That may not come so easily as being Irish for a day. Until we are ready, however, it seems unlikely that America will overcome its endemic racism and that there will truly be an American people.

To embrace the African-American experience means at least three things for nonblack people. The first is to own the extent to which the New World was built on the backs of people torn from their homes: tribal leaders sold them, Muslim slavers captured and warehoused them, nice white Christians bought, transported and resold them like cattle.

A tired old lie claims white people did not know better than to treat Africans as sub-human. Of course, they knew; they simply could not afford to let principle interfere with convenience and economic strategy. How many Christians refused to allow slaves to be baptized precisely because they knew that this would recognize their equal humanity? Oppression is always in denial of the evil it visits on its victims — ask any woman.

To focus on the history of oppression and the debt our society owes to the toil of slaves — and to the toil of wage slaves of all races — is perhaps the easiest task. Somewhat more challenging to white-held stereotypes would be to focus on the tremendous strength and courage that enabled African-Americans not only to survive brutality, but to take to the streets to claim a place owed to all Americans. This month we remember not the victims, not only the survivors, but also heroes known and unknown who changed a country.

It is chilling for me to realize that most living Americans do not remember our country before the civil rights era. Consequently, they cannot recall the change that black people made in this culture. Black History Month is important because it is a testimony to strength, courage, and the will to be free in the face of unthinking oppression. It recognizes the effort it took for all the African American scientists, scholars, teachers, parents and workers just to get to a place where they could make a contribution to a society that was and is slow to recognize a gift when it is given.

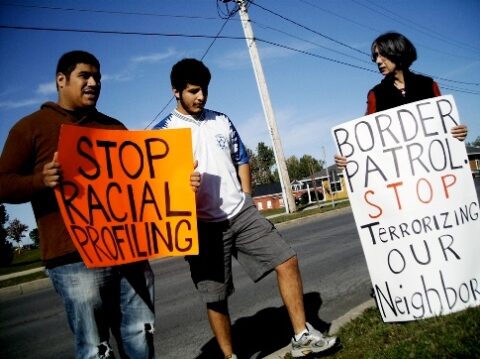

The third is probably the most challenging. Northeast Pennsylvania is still predominantly white, though that is changing rapidly. Historians have written how coal, steel, and other large employers encouraged rivalry and distrust between ethnic groups and communities: a divided work force remains weak.

All Americans need to embrace black history as our history to enable the changing population of Pennsylvania to once again become an industrial force in this country. The Latino and Asian populations are growing rapidly. Will our region sufficiently overcome its heritage of suspicion and alienation to welcome the contributions all citizens make to the commonwealth of the Commonwealth?

Until we make the effort to embrace every group’s story and accomplishments as part of how we tell the American story and perceive it as America’s strength, we will limp as a people.

The myth of the melting pot is long gone: we no longer expect or desire everyone to be somehow the same — which always meant white-acting, Christian-acting — but recognize the fabric of America as a rich tapestry. When every strand of that tapestry is honored we will be further on the way to becoming one nation.

Written By Bishop Paul V. Marshall

Leave a Reply