(Akiit.com) After working on the book for more than a decade, Haley was stuck — and desperate

I just love to get out in the ocean. You are really out there, thinking in ways you haven’t thought before. The best writing I ever possibly could do was after The Digest helped me go to Africa and Europe, and I was not known and I could just take my time and nobody was pressing me. God, I don’t know how long it took me. I was working slowly, slowly. When I had done all the research, nine years, working in between doing articles for other magazines, I was ready to write. I didn’t know where to go, didn’t know what to do. I knew I had a monumental task. And I got on a cargo ship. I went from Long Beach, California, completely around South America and back to Long Beach. It was 91 days.

There’s something about a ship. Usually I go out on freight ships, cargo ships. (I wouldn’t get caught on a liner. How can you write with 800 people dancing?) But the freight ships carry a maximum of 12 people, and they tend to be very quiet people.

I work my principal hours from about 10:30 at night until daybreak. The world is yours at that point. Most all the passengers are asleep.

I had written from the birth of Kunta Kinte through his capture. And I had got into the habit of talking to the character. I knew Kunta. I knew everything about Kunta. I knew what he was going to do. What he had done. Everything. And so I would talk to him. And I had become so attached to him that I knew now I had to put him in the slave ship and bring him across the ocean. That was the next part of the book. And I just really couldn’t quite bring myself to write that.

I was in San Francisco. I wrote about 40 pages and chunked it out. When you write well, it isn’t a question so much of what you want to say, it’s a question of feel. Does it feel like you want it to feel? The feel starts coming in somewhere around about the fourth rewrite.

I wrote, twice more, about 40 pages and threw it out. And I realized what my bother was: I couldn’t bring myself to feel I was up to writing about Kunta Kinte in that slave ship and me in a high-rise apartment. I had to get closer to Kunta. I had run out of my money at The Digest, lying so many times about when I’d finish so I couldn’t ask for any more. I don’t know where I got the money from. I went to Africa. Put out the word I wanted to get a ship coming from Africa to Florida. I just wanted to simulate the crossing.

I went down to Liberia, and I got on a freight ship called appropriately enough the African Star. She was carrying a partial cargo of raw rubber in bales. And I got on as a passenger. I couldn’t tell the captain or the mate what I wanted to do because they couldn’t allow me to do it.

But I found one hold that was just about a third full of cargo and there was an entryway into it with a metal ladder down to the bottom of the hold. Down in there they had a long, wide, thick piece of rough sawed timber. They called it dunnage. It’s used between cargo to keep it from shifting in rough seas.

After dinner the first night, I made my way down to this hold. I had a little pocket light. I took off my clothing to my underwear and lay down on my back on this piece of dunnage. I imagined I’m Kunta Kinte. I lay there and I got cold and colder. Nothing seemed to come except how ridiculous it was that I was doing this. By morning I had a terrible cold. I went back up. And the next night I’m there doing the same thing.

Well, the third night when I left the dinner table, I couldn’t make myself go back down in that hold. I just felt so miserable. I don’t think I ever felt quite so bad. And instead of going down in the hold, I went to the stern of the ship. And I’m standing up there with my hands on the rail and looking down where the propellers are beating up this white froth. And in the froth are little luminous green phosphorescences. At sea you see that a lot. And I’m standing there looking at it, and all of a sudden it looked like all my troubles just came on me. I owed everybody I knew. Everybody was on my case. Why don’t you finish this foolish thing? You ought not be doing it in the first place, writing about black genealogy. That’s crazy.

I was just utterly miserable. Didn’t feel like I had a friend in the world. And then a thought came to me that was startling. It wasn’t frightening. It was just startling. I thought to myself, Hey, there’s a cure for all this. You don’t have to go through all this mess. All I had to do was step through the rail and drop in the sea.

Once having thought it, I began to feel quite good about it. I guess I was half a second before dropping in the sea. Fine, that would take care of it. You won’t owe anybody anything. To hell with the publishers and the editors.

And I began to hear voices. They were not strident. They were just conversational. And I somehow knew every one of them. And they were saying things like, No, don’t do that. No, you’re doing the best you can. You just keep going.

And I knew exactly who they were. They were Grandma, Chicken George, Kunta Kinte. They were my cousin, Georgia, who lived in Kansas City and had passed away. They were all these people whom I had been writing about. They were talking to me. It was like in a dream.

I remember fighting myself loose from that rail, turning around, and I went scuttling like a crab up over the hatch. And finally I made my way back to my little stateroom and pitched down, head first, face first, belly first on the bunk, and I cried dry. I cried more I guess than I’ve cried since I was four years old.

And it was about midnight when I kind of got myself together. Then I got up, and the feeling was you have been assessed and have been tried and you’ve been approved by all them who went before. So go ahead. And then I went back down in the hold. I had a terrible head cold, flu-ish like. I had with me a long yellow tablet and some pencils. This time I did not take my clothing off like I’d been doing. I kept them on because I was having such a bad cold. I lay down on the piece of timber.

Now Kunta Kinte was lying in this position on a shelf in the ship, the Lord Ligonier. She had left the Gambia River, July 5, 1767. She sailed two months, three weeks, two days. Destination Annapolis, Maryland. And he was lying there. And others were in there with him whom he knew. And what would he think?

What would be some of the things they would say? And when they would come to me in the dark, I would write. And that was how I did every night, only ten nights. From there to Florida. I remember rushing through the big, big Miami Airport. Flew back to San Francisco. Got with a doctor, and he kind of patched me up.

I sat down with those long yellow tablets and transcribed. And I began to write the chapter in Roots where Kunta Kinte crossed the ocean in a slave ship. That was probably the most emotional experience I had in the whole thing.

Come around about 1:30 in the morning, you’ve been working since 10:30 and decide you’re going to take a little break. So you get up and you walk up on the deck. And you put your hand on the top rail, your foot on the bottom rail, and you look up. The first most striking thing is, man, you look up and there are heavenly objects as you never saw them before. You find yourself looking at planets at sea. And what you start to realize, you never saw clear air before. In some latitudes, down off West Africa, South America, on the night of a full moon, there are times you get into an illusion — if you could just stretch a little further you feel like you could touch it. And you are out there amidst all Gods firmament and then you stand and you feel through the soul of your shoe a fine vibration and you realize that’s man at work. That’s a huge diesel turbine, 35 feet down under the water driving this ship like a small island through the water. Still standing there, now you start hearing a slight hissing sound. You realize that’s of the ship cutting through the resistance of the ocean. With all that going on, feeling these man things and seeing the God things, that’s about as close to holy as you are going to ever get.

Edited from a talk at Reader’s Digest, October 10, 1991, four months before Alex Haley’s death

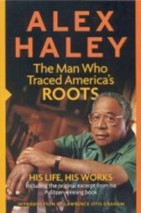

Excerpted from the book Alex Haley: The Man Who Traced America’s Roots by Alex Haley. Copyright © 2007 The Reader’s Digest Association, Inc. Published by The Reader’s Digest Association, Inc.; April 2007; $17.95US; 978-0-7621-0885-5.

Alexander Murray Palmer Haley (1921-1992) was an African American writer who was best known for his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Roots. A writer of distinction and a contributing editor for Reader’s Digest, Haley’s first major work was The Autobiography of Malcolm X, published in 1965.

Growing up, Haley had heard stories about his African ancestor, Kunta Kinte, and became interested in tracing his family to its deepest roots. It was Lila Acheson Wallace, cofounder of The Digest, who commissioned Haley to do the research that would create a groundbreaking article in the magazine. When Reader’s Digest published the first excerpts from Roots in our May and June 1974 issues, we said it was an epic work, “destined to become a classic of American literature.” That has proved to be an understatement.

In just five months after the book hit stores in 1976, more than one million hardcover copies were purchased. Since then, Roots has taken its place among the greatest bestsellers of all time as the number of copies has grown to over six million worldwide. Its impact on television was also historic: Some 130 million Americans watched at least part of the 12-hour drama, making it the highest-rated miniseries ever.

Roots changed the way we think about race in this country and profoundly affected the lives of many people, especially African Americans.

For more information, please visit http://www.rd.com/returnToRoots.do.

Leave a Reply